Category Archives: Personal Stories

Safe removal of UXO

XO (unexploded ordnance) are live bombs which failed to explode on impact. Most of the UXO in Laos resulted from cluster bombs which split apart mid-air to scatter 100s of cluster bomb units (CBUs). CBUs are also called cluster bomblets or “bombies.”

From 1964 until 1973, the Air Force dropped 288 million bombies on Laos, primarily in the mountainous Xieng Khouang province 100 miles north of the capital, Vientiane. Approximately 30% of the bombies failed to explode when they landed in rice fields, streams, bamboo groves and the like. Thus, there were more than 80 million bombies littering the Lao countryside. Those bombies killed or maimed 300 farmers and children as recently as 2011.

International teams have spent tens of millions of dollars annually to deactivate UXO in Laos for the past 18 years. At this rate of cleanup, it will take more than 2,000 years before the countryside of Laos is rid of UXO.

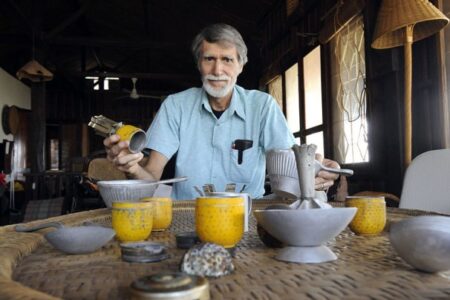

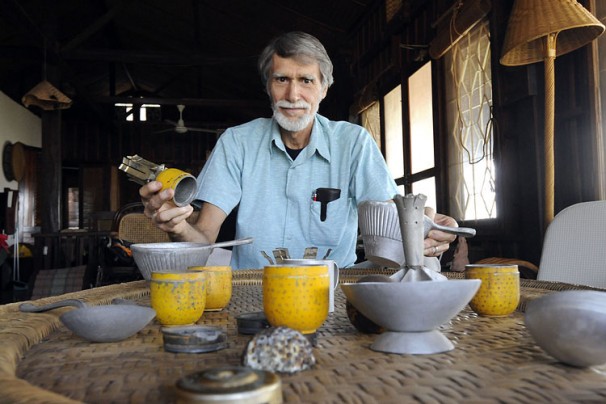

Roger Rumpf, international peace activist, dies at 68

Roger Arnold – Roger Rumpf, a peace activist who spent years in Laos and drew international attention to the problem of unexploded bombs from the Vietnam War era, died April 9. He was 68.

By Emily Langer, Published: May 11

Roger Rumpf, who died April 9 at 68 on his farm in Warrensburg, Mo., dedicated nearly his entire adult life to Laos — and to keeping that country in the American consciousness as memory of the Vietnam War faded. For years he was a sort of unofficial U.S. ambassador in Laos and a prominent advocate in Washington for Laotian issues, particularly the problem of the leftover unexploded bombs that continue to maim and kill.His death, from leukemia and acute myelodysplastic syndrome, was confirmed by his wife, Jacquelyn Chagnon.Peace had been a concern in Mr. Rumpf’s family for generations. His German ancestors came to the United States in the 19th century in part to avoid conscription in the military. His parents stood out in their farming community during the racial tension of the civil rights era — they read Ebony magazine, Chagnon said, and hired African Americans at a time when many other whites did not.During the draft for the Vietnam War, Mr. Rumpf went before his draft board and described himself as a conscientious objector, his wife said. By the early 1970s, both had joined an initiative called the Indochina Mobile Education Project — a traveling exhibit created to educate Americans about the people of Indochina and how the Vietnam War had affected them.Mr. Rumpf first went to Laos in 1978, three years after the war ended. The American Friends Service Committee, the Quaker social justice organization, had selected him and Chagnon as co-field directors for operations in Indochina.“It was such a stark thing,” said John Cavanagh, an activist who worked with Mr. Rumpf in the 1970s and today is director of the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington. “Everyone else is coming home,” Cavanagh said, referring to U.S. military personnel, “and here [were] Roger and Jacqui going in the other direction.”They stayed in Laos until 1982, then returned in 1986 for another four years.During the second tour, the New York Times reported that the entire unofficial U.S. aid program in Laos consisted of four people — Mr. Rumpf and his wife and another couple representing the Mennonite Central Committee. There was no official aid program.Mr. Rumpf and his wife lived on the Mekong River in the capital of Vientiane. They quickly understood the severity of the dangers created by unexploded ordnance, known as UXO.“It’s hard for Americans to understand,” Mr. Rumpf told Round Earth Media years later. “You walk down a path, you move anywhere, you gotta look down . . . you gotta watch what you’re stepping on, and you’ll probably be stepping on a few underneath the ground.”[continues on 2nd page of Washington Post 11 MAY 2013]